5.1: Using the "Technology as Experience" framework

Introduction

To show how the Technology as Experience framework (introduced in chapter 5) can be used to think about and inform design, two case studies are presented here. Both used it to guide their initial ideas for the design of two different websites: (i) an online fundraising site and (ii) a site that reviews men’s clothing, intended to appeal to men who do not enjoy shopping. Both were written by students as part of a graduate course in Human-Computer Interaction and hence should be noted are only hypothetical websites.

The first was written by Heather Collins when she was a graduate student at Indiana University. She used primarily the sensory and compositional threads of the framework, leading to insights on how fundraising organizations can maximize their website to tell a compelling story to a potential donor that is balanced in content and emotion. Her design combines elements of storytelling, appropriate emotional triggers, and a welcoming atmosphere to encourage potential donors to act by making a donation, volunteering their time, telling their friends, or attending a related event. Through this process, the donor can create a meaningful connection to a cause or problem directly impacting their community. The personal connection makes the online donation experience pleasurable for the user.

The second was written by Aaron Loehrlein when he wasalso a graduate student at Indiana University. He used all the threads to think about designing a website for a pleasurable experience for clothes shopping among men who ordinarily hate clothes shopping. Because the website is intended as a consumer guide for men’s clothes, and not a retail site, it encourages a more relaxed emotional interaction with its users. The website does not present clothes as part of a larger fashion trend, but describes how the clothes are likely to fit into the life of the wearer. The descriptions are meant to provide an entertaining, non-challenging experience by using simple, jargon-free language, familiar metaphors, and sarcastic humor that is never aimed at the wearer. He found the emotional and sensual threads to be particularly useful to design for this.

Applying the User Experience Framework to Online Fundraising

Heather Collins

Introduction

In an age where 67 percent of Americans use the Internet to find and purchase products—ranging from the latest bestseller on Amazon.com to a used sofa on Craig’s List—information architects and designers have an opportunity to investigate why customers find particular shopping experiences appealing or pleasurable.

While users may cite practical reasons such as the convenience of 24/7 shopping or the availability of millions of products, it is equally likely that less tangible elements—such as aesthetics, mood or a sense of personal connection—help seal the deal. For example, companies like Nike (http://www.nike.com) have begun to design cinematic, highly interactive retail sites that evoke emotion and invite customers to identify with their product “culture.” In short, these companies are designing for a user experience that goes beyond pragmatism (Wright and McCarthy, 2003).

While this approach to interaction design may seem attainable only to an organization with a cadre of Flash programmers and a healthy marketing budget, it need not be. Drawing on Wright and McCarthy’s (2003) user experience framework, this paper will address how to design for a pleasurable user experience in the context of non-profit online fundraising. The next section provides a brief background on the online fundraising environment, followed by an explanation of the user experience framework elements particularly applicable to the online donation process. The following section offers a prototype of a new online donation experience, including design concepts and scenarios. The final section discusses the benefits and challenges of the proposed design, as well as potential design trade-offs and evaluation methods.

A Brief Overview of Online Fundraising

In 2004, Americans donated between $162 million and $3 billion online to nonprofit organizations encompassing youth and family services, faith-based effforts and humanitarian and relief initiatives, just to name a few (Sausner, 2005).

According to the Pew Internet and American Life Project, the number of online donations in the U.S. has increased by 53 percent since January, 2005. The devastating effects of the 2004 Asian tsunami and recent U.S. hurricanes have prompted unprecedented levels of Internet donations to organizations like the Red Cross, The Salvation Army and CARE (Horrigan and Morris, 2005). In general, nonprofit organizations strive to make it easy for donors to give. These organizations have come to recognize the importance of integrating Web-based initiatives into their fundraising strategies because the Web enables them to reach thousands of potential donors at minimal cost.

Although there is little empirical evidence to explain why people give online versus offline, it is likely that convenience, impulse and loyalty all play a part. Interestingly, these are similar reasons people choose to shop online. In a recent study, Holt and Horn (2005) offered five factors that seem to motivate offline giving to nonprofits: (1) the organization’s mission; (2) whether the organization adds value/has a sense of responsibility to the community; (3) financial stability and transparency of the organization; (4) the quality of volunteer leadership (e.g. board, committees); and (5) the quality of staff. The authors also stressed that organizations venturing into the online fundraising domain need to explicitly invite donors to give online, offer a simple,

attractive and secure interface, and maintain open and clear communication channels (online or otherwise) with the donor to ensure that the relationship continues (Holt and Horn, 2005).

Why We Need a New Perspective

The goal of this project is to design a rewarding online giving experience from the perspective of the donor. In general, nonprofit organizations tend to be late technology adopters and many organizations have only established Web sites within the last few years. These sites typically function to provide donors, volunteers and grant-makers with information about an organization’s mission, programs and leaders. For example, the Central Indiana Community Foundation (http://www.cicf.org) is a relatively static site, and a donor has to work very hard to find how he might be able to give online. Two levels beyond the home page, the donor finds a page entitled “Ways to Give,” where he can download a donation form to mail into the organization, but not give online. This is not an uncommon scenario for many small to medium-sized nonprofit organizations.

At present, nonprofit Web sites with online giving capabilities tend to be purely functional—not unlike e-commerce sites of 10 years ago. A significant number of nonprofit organizations also use third-party vendors such as Network for Good (http://www.networkforgood.org) for online fundraising because they do not have the technical resources to manage online donations in-house. However, these services typically take the donor to a separate e-commerce interface with a different look and feel from the original organization’s Web site. Thus, it is safe to say that few nonprofit organizations have been able to design for an online fundraising user experience due to practical constraints. By applying Wright and McCarthy’s user experience framework to the context of online giving, it may be possible to better integrate the mission, vision and accomplishments of these important organizations with the online donation process. In addition, nonprofit organizations would have an opportunity to provide potential donors and friends with a balanced cerebral and emotional online experience that may entice them to donate more generously.

The User Experience Framework

On a theoretical level, Wright and McCarthy’s (2003) user experience framework recognizes that all human experiences are holistic and relational, and are comprised of a balance of sensual, cerebral, and emotional “threads.” The user experience framework is built on the goal of sense-making: that is, unifying the different threads of a situation, in this case, an online experience, to create meaning for the user. The full framework includes four threads (compositional, sensual, emotional and spatio-temporal) and six corresponding sense-making elements (anticipating, connecting, interpreting, reflecting, appropriating and recounting). For the purposes of this project, only the compositional, sensual and emotional threads will be considered.

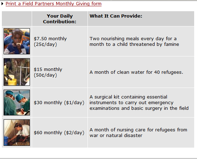

Quite simply, Wright and McCarthy’s (2003) compositional thread is the story. In the context of online giving, the donor might “interpret” or “reflect on” a story about the people and places the nonprofit organization is trying to help through special programs or services. Interestingly, this thread coincides with a common fundraising tactic of using direct mail to tell donors a story, with the hope that they will donate to the cause because they identify with or are moved by the story. The compositional thread might be considered the cerebral element of the user experience framework. In the online fundraising context, this thread may also include facts and figures related to how much the organization must spend to support a particular program, or what a $25 donation can provide. The simple gesture of providing important information to the donor may help them decide how much to give. In fact, some nonprofit organizations, such as Doctors Without Borders, do a very good job of including this information on their Web sites:

Source: Doctors Without Borders--http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/donate/what.cfm

On the other hand, the sensual thread is concerned with connecting the user with the experience—and keeping them there—by coordinating the look, feel and atmosphere of the site. The sensual thread operates at the subconscious level, and in the present case would help the donor determine if she feels a sense of belonging or alienation, comfort or discomfort, trust or suspicion. As previously mentioned, many nonprofit organizations outsource the online donation portion of their site, resulting in the donor being brought to a site with a different interface to complete the transaction. While many organizations will not be able to control all the sensual elements of the online donation experience, they may be able to enhance the aesthetics of their Web site by using dynamic elements such as coordinated photos, short video and audio, and thorough basic design elements of layout, color and font.

Finally, the emotional thread is concerned with the user’s reaction to the experience; in other words, how it makes them feel. For example, the donor may feel motivated to make a difference by attending a fundraising event; she may be angered at the level of poverty in her neighborhood; he may feel proud to be doing something proactive to help; or she may feel frustrated because the organization is trying to “sell” itself via a flashy interface. Within the online fundraising model it is also likely that the emotional thread and the compositional thread will overlap due to the inherently emotional nature of stories describing people in need of food, shelter or medical care. In other words, the emotional thread may have more than one meaning.

To summarize, the user experience framework offers nonprofit organizations the opportunity to present potential donors and supporters a more holistic online experience by balancing storytelling with emotional and sensory elements. While many aspects of Wright and McCarthy’s (2003) framework have been useful in the context of online fundraising, it is worth noting the framework has some ambiguities. For example, it is unclear exactly where the six sense-making elements fit into the four threads and whether they are mutually exclusive. In addition, it seems that the threads overlap. For example, it may be difficult to explicitly distinguish between the sensual thread and emotional thread, and in the present case, one may find common elements in both the emotional thread and the compositional thread.

Design Concepts and Scenarios

Wright and McCarthy’s (2003) user experience framework provides structure to a set of design elements unique to the domain of online fundraising. Drawing on the insights of the above user experience framework analysis, recent research on donor perceptions of the nonprofit sector, and inspiration from other online environments, the following scenario and design concepts are proposed:

Scenario

According to a recent study by Public Agenda, a nonpartisan civic engagement organization, the typical American donor (who gives about $300/year) tends to trust and admire small, local nonprofit organizations, decides to give to an organization based on a “gut-level interest” in the cause, and values a personal connection with the charity (Arumi, Wooden and Johnson, 2005). The authors also found that donors were turned off by flashy marketing campaigns because they felt as if the organization was trying to sell them something, and were wary of organizations that spent large sums on advertising when those funds could have been used to fulfill their mission (Arumi, Wooden and Johnson, 2005).

Based on these findings and the assumptions that (1) donors want to know where their money is being spent, and that even a small contribution can make a difference; and (2) donors want to have choices in the types of programs or projects they support, a new online fundraising paradigm is proposed. This Web site will enable multiple nonprofit organizations within a specific geographic region (e.g., city, county) to post detailed information about programs or projects that require assistance. The overarching goal is to enable individual or corporate donors to contribute to organizations in their neighborhood, or to organizations addressing specific issues like homelessness, domestic violence, historical preservation or at-risk youth. Figure 1 below depicts a prototype of this type of site, “Boston Gives.”

When a donor visits Boston Gives, she may login to her profile, or search for a project based on geographic region (zip code) or by cause/issue. She may also browse through all currently active projects. On the project page (see figure 2), the donor will learn the story behind the project, including the neighborhood and people it will serve. Once the donor decides to give, she will be brought to an e-commerce interface, but one which is fully integrated with the Boston Gives site. The page will shows details about the specific project she is contributing to, the current financial status of the project, and links to news and updates related to project milestones.

Figure 1: Prototype of “Boston Gives” homepage

Design Concepts

Simple, clear interface First and foremost, a simple, clear interface will enable the donor to decide what to do on the site—whether it is donating money, searching for projects based on geographic region or cause, or logging into their profile. Some nonprofit organization Web sites offer donors information on every project and news item, effectively creating information overload. In addition, unlike typical nonprofit Web sites offering online donation capabilities, Boston Gives would integrate vital information about the project throughout the donation process. Before giving, a donor can learn about the project’s goal, the organization leading it, and neighborhoods the project will impact (See Figure 2). Finally, the simple design will help Boston Gives balance factual information (what $25 will provide) with emotional triggers, such as a short film about the project.

Inspiration for including a short film in the prototype came from Canadian singer Sarah McLachlan’s Web site, (http://www.worldonfire.ca/). Through a series of simple, highly emotional clips, McLachlan documents how she took $150,000 typically used to produce a music video and donated it to charities around the world. The look and feel of her project indicates that organizations can keep it simple and still create a moving experience.

Source: Screen shots from video at http://www.worldonfire.ca

Engaging: Tells a story The most salient component from Wright and McCarthy’s (2003) user experience framework is the compositional thread, or story, told through short, narrative descriptions of the project as well as some form of multimedia. The authors view “design as conversation with a situation,” with the purpose of engaging the user and empowering him to create meaning from the experience. Nonprofit organizations can choose how they want to present their story on Boston Gives, and in essence, help design for a user experience. They may opt to tell their story through multiple short videos, still images, audio, text or some combination of multimedia.

Transparency and Feedback: Where does money go? Another important design element is the transparency and feedback mechanism included on the project page. As previously mentioned, donors trust nonprofit organizations when they maintain transparency and open lines of communication. For example, Heifer International (http://www.heifer.org/), enables donors to buy a farm animal— a cow, lamb, flock of chicks, a trio of rabbits—which are then sent to families in underdeveloped countries. The site does an excellent job of explaining exactly what your money buys (e.g., $120 buys the gift of a goat) along with short descriptions of how the animal will help the family or community.

In addition, the Boston Gives project page offers donors two feedback mechanisms—updates on how the project is progressing, and a status bar indicating how much money has been raised, and how much more support the project needs. Again, this helps instill a sense of trust between the organization and the donor, as it assures the legitimacy of the organization. Furthermore, the donor feels that their donation is actually making a difference.

Locally based, multiple projects and causes The final design element is based in on the idea that donors want to have choices—choices about what kind of projects they support, the location of the projects, and how they want to give. By enabling donors to support specific initiatives, nonprofit organizations may find that donors are more fully engaged in the issue. This may result in more generous financial donations as well as “spillover effects”: donors may in addition volunteer their time or tell their friends about the project.

Figure 2: Prototype of “Boston Gives” Second Level Project Page

Discussion

According to Wright and McCarthy (2003), the process of sense-making ensures that we view an experience through the eyes of a person. By applying the user experience framework to the context of online fundraising, organizations have an opportunity to tell a compelling story to a potential donor that is balanced in both content and emotion. The combined elements of storytelling, appropriate emotional triggers, and a welcoming atmosphere throughout an online fundraising environment like Boston Gives will encourage donors to act by making a donation, volunteering their time, telling their friends or attending a related event. The online experience helps the donor create a meaningful connection to a cause or problem directly impacting their community. It is this personal connection which makes the online donation experience pleasurable for the user.

On a more practical level, a site like Boston Gives may be appealing to donors due to its simple interface, and because it provides multiple, obvious options for action. Often, nonprofit organization Web sites provide so much information about the organization and its programs that the donor does not know where to begin. The donor may read about a certain project, feel engaged, but then be distracted by a different news item or navigate to an external link. This translates into missed donations for the organization. Furthermore, Boston Gives may provide small nonprofits or those with very limited resources or technical expertise with a place on the Web for the first time.

It is difficult to predict whether an online fundraising Web site like Boston Gives would be successful, or how users would react to a centralized site with hundreds of worthy causes to choose from. In order to evaluate the proposed design, it would make sense to solicit feedback from nonprofit IT professionals. In addition, it would make sense to conduct a pilot study in a city with a vibrant nonprofit community, such as Boston, MA or San Francisco, CA. By working closely with a diverse group of users, interaction designers can assess whether a model like Boston Gives would in fact offer donors a holistic, integrated online giving experience.

As indicated by a recent study, nonprofit organizations have an opportunity to utilize online environments in order to fulfill their mission. Designing for an online donation experience that balances cerebral and emotional elements will help nonprofit leaders keep sight of the “visceral nature of donors’ charitable impulses…[donors who] prefer an active rather than passive engagement in charities…and want to see the effects of the organization’s work in their local communities” (Arumi, Wooden, and Johnson, 2005, p. 31).

References (Print)

Arumi, A. M., Wooden, R. and Johnson, J. (2005). The charitable impulse: A report from Public Agenda. Retrieved on November 13, 2005, from http://www.publicagenda.org/research/research_reports_details.cfm?list=94

Forlizzi, J. and Battarbee, K. (2004) Understanding Experience in Interactive Systems. DIS04 Conference Proceedings, Cambridge, MA, August 2004, 261-268.

Girgenshon, A. and Lee, A. (2002). Making web sites be places for social interaction. Proceedings of the 2002 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work. 136-145.

Holt, G. E. and Horn, G. (2005). Taking donations in cyberspace. Bottom Line: Managing Library Finances, 18(1), 24-28.

Horrigan, J. and Morris, S. (2005). 13 million Americans made donations online after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Retrieved on November 26, 2005, from http://www.pewinternet.org/

Metz, C. (2005, Nov 22). Online donations to the rescue. PC Magazine. Retrieved on November 27, 2005, from http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,1759,1879807,00.asp

Perry, S. (2005, Nov 25). Survey finds spike in online giving prompted by hurricane donations. Chronicle of Philanthropy, 17(28). Retrieved from http://philanthropy.com/free/update/2005/11/2005112401.htm

Pooley, E. (2005). Rethinking how we give. Canadian Business, 78(16). Retrieved on November 13, 2005, from Academic Search Premier.

Sausner, R. (2005). Getting to one-click giving. University Business, August 2005, 8(8), 60-63.

Sincliar, M. (2005, Nov 1). Relief, bequests push the NPT 100. Nonprofit Times: Special Report. Retrieved on November 20, 2005, from http://www.nptimes.com.

Wallace, N. (2004, Jan 22). Charities try new year-end online appeals. Chronicle of Philanthropy, 16(7), 28.

Wallace, N. (2005, June 9). A surge in online giving. Chronicle of Philanthropy, 17(17), 7-12.

Wright, P. and McCarthy, J. (2003). Making sense of experience. In Blythe, Monk, Overbeeke and Wright (2003) Funology: From usability to user enjoyment. Pre-final chapter retrieved from http://www-users.cs.york.ac.uk/~pcw/

References (Online)

CARE USA: https://donate.care.org/05/170420990000/?source=170670020000 Central Indiana Community Foundation: http://www.cicf.org/ Charity Navigator: http://www.charitynavigator.org/ Doctors Without Borders: http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/donate/what.cfm Heifer International: http://www.heifer.org/ Intermediate Technology Development Group (now Practical Action): http://www.itdg.org/ McLachlan,

Shopping for Clothes: A Pleasure?

Aaron Loehrlein

Introduction

This case study describes a website that reviews men's clothes. It is designed to appeal to men who do not enjoy the process of selecting and purchasing clothes. The website is a consumer guide to men's clothing, and as such allows for a more relaxed emotional atmosphere than a site that retails clothes and accessories. The website does not present clothes as part of a larger fashion trend, but describes how the clothes are likely to fit into the life of the wearer. The descriptions will design for an entertaining, non-challenging experience by using simple, jargon-free language, familiar metaphors, and sarcastic humor that is not aimed at the user.

This conception for this website is partially in response to websites such as Guyshop <http://www.guyshop.com>, which create a user experience as stylish as the products that they sell. While this sort of stylishness is fun to look at, for many users it creates a dynamic that discourages the actual purchasing of garments and other items. One reason for this is that the clothes all seem to belong together on the website, instead of inviting the user to consider what he might look like if he were to wear a particular garment. The website described in this paper focuses on how a user might think about clothes, whether they are in a shop, his closest, or on his person. Because it deals with men's clothes, the website should be almost exclusively of and by men. It should be primarily for men, but not exclusively so (women should feel encouraged to use the website).

Although the website can design for the experience of selecting clothes, it must acknowledge that clothes shopping is a highly familiar experience in western culture. No matter how the clothes are presented or discussed, they must be selected, purchased, and worn. This well-established experience should inform the strategy for designing the website.

The User Experience Framework

The framework used to inform the design of the website is the User Experience Framework, by Wright and McCarthy (2003). This framework identifies four "threads" by which user experience may be designed: compositional, sensual, emotional, and spatio-temporal. Because the experience of shopping for clothes is an emotional experience that is based on the sensuality of clothes, the sensual thread and the emotional thread are likely to be the most important.

It would seem as though the emotional thread cannot be engineered directly, but acts as more of a dependent variable that is affected by the other three threads. For example, if one wanted to design for a tranquil emotion, one could use soft greens and yellow and display images of fields. Similarly, if one wanted to design for an emotion of fear, one could create a website that featured fake blood and ominous music. However, in both cases, what is really being designed is sensuality. One could use the compositional thread to create emotions, perhaps by leading to a critical piece of information over multiple web pages in order to create suspense. Wright et al provide the example of referring to a movie star as one means of designing for emotion that does not necessarily rely on the other three threads. This seems to suggest that the emotional thread is in practice a "miscellaneous emotion" thread. That is, it is concerned with emotions that do not result from sensual, compositional, or spatio-temporal factors.

The concepts and scenarios of using the proposed website will be explained in terms of the four threads of the User Experience Framework.

The Emotional Thread

The website does not actually sell garments or other products. It reviews garments, which the user might then purchase elsewhere. Because the user that is intended for this website is characterized by fear of clothes, the non-commercial aspect of the website should serve to reduce the pressure of selecting and purchasing clothes.

The website Television without Pity http://www.televisionwithoutpity.com describes a "complex love/hate relationship" that its users have with the website's primary topic, television shows. Clothes probably inspire a similar love/hate relationship among people in general. However, among the website's intended audience, clothes probably do not inspire as strong a emotional reaction as do television shows. For example, it is unlikely that there would be much use for a forum in which users could debate the merits of a particular sweater. In addition, there are simply too many specific articles of clothes for each one to appear on the website. Therefore, only a representative cross-section of garments will be reviewed.

Overall, the site should not require a great deal of commitment from the user. For example, there could hypothetically be a form where the user selects his skin, hair color, and eye color from a variety of models. The website might then pass this information to a back-end database that determines the user's best color for garments. However, the people for whom the website is intended would probably not want to go through this process. For one thing, the type of user for which the website is made does not like looking at models (at least not male models). And he certainly takes no pleasure in comparing his body to the bodies of models. This approach, and others like it, are potentially useful, but fall outside the user experience for which the website is designed.

For these reasons, the website is unlikely to have many interactive features. The reviewers will post fairly short reviews of articles of clothing that have been selected arbitrarily. The reviews will be highly opinionated and not always fair. The purpose of this approach is to encourage the user to think about the validity of the review. The act of forming an opinion review is likely to entail forming an opinion about the garment under review. If the user becomes comfortable in forming such opinions, the website has achieved its purpose. The website should aspire to discussing the clothes in a way that is informative without incorporating much jargon. Even terms as basic as "inseam" might be off-putting to the intended audience. When discussing a cotton T-Shirt, mention the thickness of the fabric in the specifications, but not in the review. Instead, the review should talk about how hot it was (or is likely to be). Instead of talking about how well the garment breathes, the reviewer should describe how clammy he felt.

The home page of the website will briefly discuss the frustrations involved with clothes that look good in the store, but that end up not being worn once they are purchased. The tone of text should be no-nonsense, but also entertaining and engaging.

The Sensual Thread

The website will not have many graphics and probably no sound effects or multimedia. This is not to avoid a sensual experience, but to create a specific type of sensuality. The tone adopted in the text will be the primary instrument of sensuality. It should take into account the user's fear of clothes and the shopping experience without ever explicitly acknowledging it (as this would shame the user). Instead of concentrating on how clothes create a fashion ideal, to which the wearer could aspire, the site should concentrate on how well clothes fit the person. The website should implicitly convey the idea that the user should not have to expend effort in order to successfully wear a garment. The website will acknowledge fashion constraints, but will tend to soft-pedal them. For example, although certain colors might not look good on a person, in practice the user does not need to wear just the right color for him. Also, there are some colors, such as black, that look good on nearly everyone.

The following are samples of reviews from other websites, and how their tone creates a sensual experience.

From Television without Pity, a review of an actor's visual style in a particular television episode:

Ace, Sep, and numerous posters have shredded David Boreanaz's "Irish accent," so I'm saved the trouble of doing it here. I'll reserve my commentary for the hair. Did you ever see that Simpsons Halloween special where Snake died and Homer got his hair? It sort of looks like that, like someone scalped someone else and put the whole mess on top of Angelus's head. Only Snake's hair gave the wearer an actual personality. With the traditional attire, the hair, the mustache, and the accent, Angelus is about as intimidating as a Teletubby.

URL: http://www.televisionwithoutpity.com/story.cgi?show=12&story=3653 &limit=all&sort=

The review uses popular culture references in order to discuss fashion in terms that a layman can understand. It also uses sarcastic humor in order to emotionally engage its audience.

From Robert Christgau's Web Site, a review of a popular music album:

Madonna: Erotica [Maverick/Sire, 1992]

OK, everybody, let's use our imaginations, shall we? It may be a little hard at first, but if we try we can have lots of fun. To start, let's pretend that we have nothing against dance music--that instead of fixating on impersonal and mechanical and all those obvious things we can just enjoy it for what it is, as innocently as babes. Come on now, really try. Got it? Good. Because now I'm going to suggest something even harder--that we pretend we've never heard of Madonna. I know that's like asking you not to think of a purple polar bear, so just pretend to pretend, if you know what I mean, which as good postmodernist children you do. Now, put the record on. Hear those bass and synth beats? Sinuous and subtle and sexy, aren't they? How 'bout the faux-Arab electro on "Words"? And aren't the techno effects all nice and cheesy-futuristic? The singer doesn't have great pipes, but because she's too hip to belt (this time), she doesn't need them. She's in control, all understated presence and impersonal personality except when she's flashing some pink. Also, not counting that "Love your sister, love your brother" thing, the lyrics are not stupid. I love the rap where the boast turns out to be a lie. And whoever thought of recording the breakup song through the phone hookup was pretty smart, wasn't he or she? She, I bet. A find. A

URL: http://www.robertchristgau.com/get_album.php?id=2208

This review distinguishes between Madonna as a celebrity and the music on her albums. It also makes a distinction the objective merit of dance music, the attitude which with the music is frequently received by the target audience. Again, the review makes use of sarcastic humor, this time directed in a playful manner at the audience. The reviewer appears to implicitly suggest that his audience ought to be able to appreciate this album for its merits, but is unlikely to be able to do so. Since the underlying emotion when it comes to clothes is assumed to be fear, this type of sarcasm directed at the audience might not be appropriate for the website about clothes.

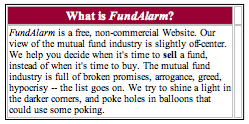

classFrom Fund Alarm http://www.fundalarm.com, a critique of recent actions taken by the management of a mutual-fund company:

- Remember that obnoxious kid in grade school who could never accept losing, and who was always asking for a "do-over," and remember how nobody had any respect for him and how, eventually, nobody wanted to have anything to do with him?.....Hold that thought for a moment.

- Back in October, we reported that shareholders rejected an attempt by TIAA-CREFF to push through a huge management fee hike on nine of its mutual funds.....Now, TIAA-CREF is going to try again: It has scheduled a re-vote on the fee increase, believing that "certain large, institutional shareholders might be willing to re-examine the proposal."

- From the TIAA-CREF Web site (October 12, 2005) :

![]()

How deliciously ironic: TIAA-CREF initially lures investors into its funds with low-ball management fees, then tries to quadruple its fees, then won't accept its shareholders' "no" vote, then tries again to ram through the fee hike.....Now TIAA-CREF unveils a survey that finds only 9% of Americans believe financial services companies are "very trustworthy".

URL: http://www.fundalarm.com/hilights.htm

This review uses an extended metaphor to explain a fairly complicated action taken by a financial company. The metaphor, that of a petulant child, is likely to be easily understood by the vast majority of the people who visit Fund Alarm's website. This example illustrates how topics that seem forbidding, such a proposal to restructure the finances of a mutual fund company, can be made fairly clear (if biased) through the use of simple language, familiar metaphors, and sarcastic humor.

Of course, the website will also feature images of clothes. The models should wear the clothes in a way that expresses the user's likely experience of wearing the clothes. The models should look like ordinary people. For example, some clothes may not fit a certain model quite right because he is too pudgy. The models should not pose like models. However, models also should not pose the way that people ordinarily pose for photographs (smiling, looking at the camera, etc.). In some images, a model might look awkward, but he should not convey the impression that he is uncomfortable with their picture being taken. Rather, they should convey the impression that their picture is not being taken at all. They should emulate the way in which "normal" representative of the target demographic act when they are going about their business.

The Compositional Thread

The website should project a feeling of momentum. Therefore, the phrasing should be economical. The text should be entertaining as a primary concern and informative as a secondary concern. The home page would be divided into a "main" section and a "supplemental" section. The main section should be simple and static. It would consist of a menu of types of garments, which link to lists of garments rated. These lists may include summaries of reviews, but should not include the full review or most of the garments' specifications. This list should be sortable by manufacturer, price, overall rating, and the date the review was written (which should be the default order). Ideally, a search box should also be provided.

The supplemental page should include any resources that change fairly regularly. For example, the supplemental site might feature "top ten" lists (or bottom ten lists) that represent an idiosyncratic category, such as "Top Ten Shirts to Wear to a Party Where You Only Know One Person ($20 or less)". The lists should be funny, but useful. For example, the preceding list should not include joke entries such as "this shirt will make you look like a CIA agent on holiday, so you can arrest anyone who annoys you". Older resources should be archived, not deleted. The composition of the website should give the user confidence that he or she can find desired information quickly, but should also surprise the user with new types of resources.

The simplicity of the site structure might in some cases detract from the user's compositional experience, since the relative sparseness of web pages might tend to result in pages that consist of very long lists. For example, Robert Christgau's Web Site consists mainly of a catalog of albums that he has reviewed. The home page links to the catalog, which is for the most part divided into three submenus, each representing different features by which to browse albums (artists, labels, etc.). Each of the submenus is divided alphabetically. For example, the option 'M' on the submenu "Browse Artists" links to a page that consists of a list of artists whose names begin with 'M', sorted alphabetically. Selecting an artist takes one to a page that consists of the artist's albums, in chronological order. Although navigation between pages is simple, navigation within a page can feeling overwhelming. For example, the 'M' page of artists consists solely of a list of 471 artists. When printed, this page takes up nearly ten sheets of paper. Scanning a list of so many items is likely to be an experience that is more frustrating than pleasurable. Television without Pity's website has similar problems. The main page links to a list of the 161 television shows reviewed on the site. The main page of each television show consists of a list of episodes reviewed, which frequently number in the dozens, or even hundreds.

One way to break down longs lists of this sort is to allow the user to browse for items according to more than one feature at a time. For example, the user could link to a dynamically-created page that consists of trousers in a specified price range.

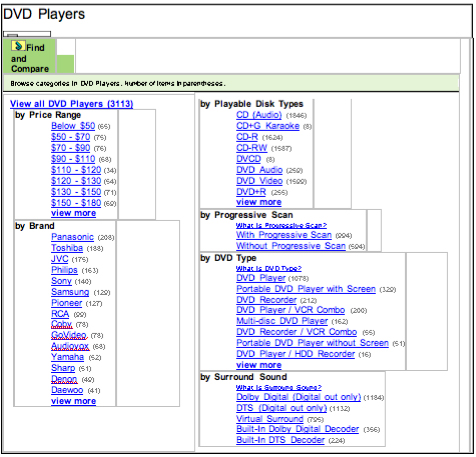

Epinions http://www.epinions.com offers something like this when they allow users to search by more than aspect of a product, as can be seen in the figure below. However, Epinions does not allow the user to search by multiple criteria simultaneously.

URL: http://www.epinions.com/DVD_Players

If many lists tend to run too long, lists that are constrained by multiple criteria might be too short, or have no members at all. In that event, one potential solution might be to automatically include similar results from just outside the criteria. For example, if "shirts" and "$20-$40" yielded only two results, the website could add to the list shirts that cost under $20, or from $40-$60.

The Spatio-Temporal Thread

According to Wright et al, the users who are in a hurry may feel confined in the space they occupy. Because the website does not sell products, the user is likely to feel less rushed than he or she would on sites that offer temporary sales. In addition, the simplicity of the structure may help the user feel relatively unconfined. The website has no "private" features, such as a shopping cart or a forum in which to post messages.

Making Sense in Experience

The user experience framework provides six concepts by which a user's experience unfolds. They are, in order, anticipating, connecting, interpreting, reflecting, appropriating, and recounting.

Anticipating

The user will likely come to the website with a desire to be entertained and to learn more about clothes. Because the site does not allow the user to purchase articles of clothing, repeat users would not come to the website expecting to make a purchase decision. First time users might be under the impression that the website has a retail function until they see the home page banner, which succinctly describes the website's mission. The following banners serve as models:

Robert Christgau's Web Site

Hi. I'm Robert Christgau. I've written about rock and roll, popular and semipopular music, and popular culture since 1967. This is my website, and herein you will find as much of my writing as we can put up. This includes my Consumer Guide to over 12,000 records, my books, essays from my Village Voice Rock&Roll& column, other music writings, book reviews, and more.

URL: http://www.robertchristgau.com/ URL: http://www.fundalarm.com/

Both Robert Christgau's Web Site and FundAlarm communicate the purpose of their websites in about seventy words. Each website's home page also uses graphics sparingly, which gives the user a sense of simplicity and focus.

Connecting

Because the website has a deliberately muted sensuality, the user will likely connect with the few images that exist. The textual content of the reviews is the focal point of the website. In contrast, the pictures of the garments and the men who model them are not intended to particularly engage the user. However, they are intended for the user to literally connect them with his (or possibly her) own life.

Interpreting and Reflecting

The interpreting and reflecting aspects of the experience sense-making process appear to be particularly difficult to design for. They seem to represent the point at which the user gains an understanding of the website's purpose, style, and content. It is to be hoped that the user will have the experiences that were described under the four threads.

Appropriating and Recounting

The website should use each of the threads of user experience in order to help the user appropriate knowledge about clothing and a vocabulary by which to conceptualize and evaluate clothing. The ultimate goal is for the user to be able to recount that experience when actually shopping for clothes. This website is intended to provide conceptual tools that can be generalized to the process of purchasing clothes, including the means by which to engage that experience with feelings of confidence rather than uncertainty and fear. Although those feelings would be difficult to measure, they are the ultimate criteria for evaluating the success of the website.

Conclusion

This case study has made use of the User Experience Framework in order to describe a hypothetical website that helps men find pleasure in shopping for clothes. It found the emotional and sensual threads to be particularly useful, since the asset of this website is not in the subject matter of its content, but in how that content is expressed.

It would appear that designing for a pleasurable online shopping experience is more difficult that designing pleasurable physical products. While a physical product can be touched and handled, the online shopping experience forces the user to experience products only in an abstract way, i.e., how they are represented on the website that sells them. Also, because the shopping experience inevitably involving the user parting with some of his or her money, shopping will always include a certain amount of tension that would not necessarily be found when simply interacting with a product.

References

Epinions. URL: http://www.epinions.com/. Accessed December 2005.

Fund Alarm. URL: http://www.fundalarm.com/. Accessed December 2005

Guyshop: mens fashion, menswear, golf gifts, Unique gift ideas, gift ideas. URL: http://www.guyshop.com/. Accessed December 2005.

Norman, D.A. (2003). Attractive things work better. In Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

Robert Christgau's Web Site. URL: http://www.robertchristgau.com/. Accessed December 2005

Television Without Pity. URL: http://www.televisionwithoutpity.com/. Accessed December 2005

Wright, P., McCarthy, J. (2003). Making Sense of Experience. In Funology: from usability to user enjoyment, by Blythe, Monk, Overbeeke and Wright.